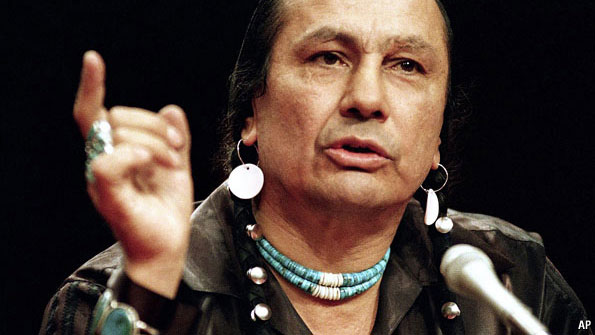

Russell Means

Russell Means, an American-Indian activist, died on October 22nd, aged 72

His own God-given sovereignty blazed inside him, igniting the Indian-rights movement he led for several decades. He was pure Oglala Lakota, born in the sacred Black Hills of South Dakota, and with the build of a chief, strapping and tall. His hard, dark eyes seemed to stare from another century, re-running ancient battles; his handsome face was crossed with scars, though these were less ritual marks than the souvenirs of bar-room brawls in Sioux Falls or San Francisco. The long braids (never cut, for hair carried memories), the beads, the leather: everything cried out his heritage. But being Indian, he fiercely said, didn’t mean dressing in feathers like a bird and going to a pow-wow for a couple of hours. No Indian was authentic if he wasn’t as free as his ancestors had been.

He was far, very far, from that. The ramshackle Pine Ridge reservation, his birthplace, was still “prisoner-of-war camp 344” in Pentagon records. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), which oversaw such slums, was a den of corruption and incompetence. The modern tribal governments were mere puppets and collaborators. Indians everywhere (never “Native Americans”, another colonisers’ word) had been robbed, corralled and turned into cowed, self-loathing lemmings in white schools. Every treaty made by the white man with the Indians had been broken. America was “the biggest liar in the world”.

He defied the lies in small ways and large. Not for him a driving licence or a fishing permit; the land he drove on, the river he fished in, belonged to his people anyway. For 21 years he paid no income tax. He refused to carry an Indian ID card. He ran on an activist platform for tribal, state and national office (for the Libertarian Party, in 1987), though never successfully. All this time he was the leading member of the American Indian Movement (AIM), as charismatic as he was divisive. The movement had turned him, at 29, away from a drifter’s life and towards a cause.

At AIM he organised a succession of publicity stunts, including the occupation of Alcatraz Island; the seizing of a replica Mayflower in Boston Harbour on Thanksgiving Day, 1970; a prayer-vigil on top of Mount Rushmore, on Lakota holy land; and the occupation and trashing of the BIA’s Washington offices in 1972. All were tasters for the most daring stunt of all, the occupation in 1973 of the hamlet of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge reservation, where in 1890 around 300 Lakota had been killed by the American army. Chilled and starving, but steeled by the free-walking spirits of the dead, Mr Means and 200 others held out, through blizzards and machinegun fire, against massed federal guardsmen for 71 days. He tried to dictate the terms of the surrender; the Nixon administration naturally reneged on them.

An arrow to the sun

Most of the time he was angry, an anger so intense that it was almost uncontrollable. His drinking did not help. Violence dogged him. Enemies, probably agents of the BIA, tried to shoot him. He got into fights, had spells in jail, married and then neglected several women in the style of the head-buck wandering male. His years in AIM were chaotic; he resigned six times before the movement split. While other groups, blacks and women, surged ahead, America’s Indians went nowhere much. In 2007 Mr Means and several others withdrew from the United States to form the Republic of Lakota, covering thousands of square miles in five states. Not even brother-Sioux would recognise it; but their freedom was too firmly mortgaged to white men.

He lamented that his people had no natural allies: not Marxists, for they were rationalists who reduced men to machines; not Christians, for their notion of God was incompatible; not even blacks, for their experiences of repression were too different. The revolution he wanted was unlike anyone else’s. It was the revolution of the medicine wheel, the sacred hoop of life, in which all things ended as they began: in which the world was turned slowly but beautifully backwards, towards the freedom in Nature the ancestors knew.

He himself, though, went westwards, to Hollywood. In “The Last of the Mohicans” and Disney’s “Pocahontas” in the 1990s he played the sort of wise, far-seeing chief he should have been, had everything been different. He became the standard Indian, sympathetic enough, but speaking the white man’s script under the white man’s direction. Whenever his pride galled too much, he walked out.

As Chief Chingachgook in “Mohicans”, standing on a mountain top, he commended his dead son to the ancestors, crying that he would fly towards them like a swift arrow into the sun. All dead warriors went that way. So, in time, would he. But loudly and often he vowed to return as lightning, zapping to ashes in a wild, free blaze the White House and all it stood for.

No comments:

Post a Comment